Why “Smart Finance for Smart Buildings” won’t be enough to renovate Europe

The Clean Energy for All Europeans package projects buildings to play a pivotal role in the EU energy transition. The Commission sees the non-legislative initiative “Smart Finance for Smart Buildings (SFSB) as a major driver in the transformation of the emerging energy renovation market from a market of shallow renovation financed by grants towards a self-sustained market delivering zero energy buildings.

Could this be a wishful thinking?

The initiative is made of three pillars; each of them aims at addressing one set of risks through innovative instruments. If effectively implemented, the SFSB would allow for:

- financial de-risking through national financial platforms which would play a role of risk sharing facilities. The platforms would bundle EU funds and deploy attractive and accessible energy renovation loans leading to increased private investments in energy renovation;

- technical/technological de-risking through the local/regional one-stop-shops which would play a role of energy renovation facilitators. They would facilitate bundling small projects into larger ones making them more attractive for banks and industrialised energy renovation solutions leading to economies of scale; and

- behavioural de-risking through the expected changes in the perception of energy efficiency investments which could result from the tailored information on energy renovation provided by various EU/national platforms to different market actors

The de-risking activities associated with the proposed instruments (risk sharing facility, energy renovation facilitator, information platforms), will certainly contribute to increase the size of the existing market of shallow renovation, especially in Member States with an already existing technical capacity. Yet, experience from the most advanced Member States in the renovation of their building stocks show that providing finance and assistance to bundle small projects into larger ones, is not sufficient to create the demand for ambitious energy renovations at the scale needed.

Overall, the SFSB is a major step forward to mobilise private financing for energy renovation and to facilitate access to capital to local actors. However, as shown in a recent report, for the initiative to deliver on its expectations and for the EU to deliver on its energy transition the regulatory framework must be significantly strengthened by requiring owners to undertake ambitious energy renovations of their buildings and by ensuring the cost-optimum methodology leads to ambitious energy renovation.

The initiative is also unclear about how EU funds would be bundled with ETS and EEOSs revenues as well as with the existing tax credits schemes at national level. Without this clarification, local actors might well be confused and the use of ETS and EEOSs revenues in the form of grants may well continue to support shallow renovation. Furthermore, uncertainties about the availability of EU funds for the period 2021-2030 and the lack of ambitious energy savings target for 2030 may increase the perceived risks by investors and make investments in energy efficiency even less attractive than they are today. Last but not least, despite the number of instruments tackled by the Clean Energy Package, the Commission’s legislative proposal does not propose an integrated framework for buildings. Provisions on reducing energy consumption of existing buildings are kept fragmented across several EU instruments leading to a possible overlap and double counting of savings and making enforcement of the implementation rather challenging at local level.

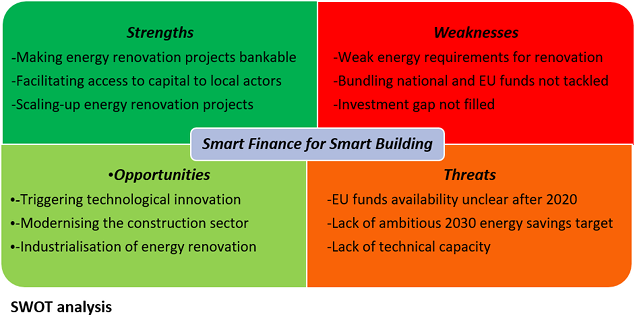

The on-going debate at the Parliament and the Council must tackle the identified weaknesses and threats of the SFSB (see figure) to ensure that the de-risking framework proposed under the SFSB is not at risk of failure.

This Column was published for the first time on May 16, 2017 on eceee